| Author | (trad.) Sun Tzu |

|---|---|

| Country | China |

| Language | Chinese |

| Subject | Military strategy and tactics |

| 5th century BC | |

| Text | The Art of War at Wikisource |

The Art Of War

Sun Zi - Download as Word Doc (.doc /.docx), PDF File. Special event and gave importance to Sun Zi’s Art of war. 6 SUN TZU ON THE ART. Bahasa indonesia. Sun Zi Bingfa (Hanyu Pinyin: Sūnzĭ Bīngfǎ), atau dikenal pula sebagai Sun Tzu Art of War, adalah sebuah buku filsafat militer yang diperkirakan ditulis pada abad ke-6 oleh Sun Zi. Sun Tzu terknal karena 13 Prinsip perangnya, Konon orang membaca 13 prinsip perang Sun Tzu dapat memenang 1000 pertempuran Perang. 1.Kalkulasi Meneliti 5 fundamental penting dalam perang yaitu Jalan, Iklim, Lapangan peperangan, Kepemimpinan lawan, dan strategi lawan. Pada posting ini kami akan memberikan terjemahan 13 BAB dari buku Art of War Sun Tzu yang di terjemahkan dari buku aslinya yang berbahasa tiongkok dan telah. The Art of War by Sun Tzu, the most important and most famous military treatise in Asia for the last two thousand years, with side-by-side translation and commentary, cross references, and PDF and text downloads of the full book. The Art of War is an ancient Chinese military treatise dating from the Spring and Autumn period. The work, which is attributed to the ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu ('Master Sun', also spelled Sunzi), is composed of 13 chapters.

| The Art of War | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 孫子兵法 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 孙子兵法 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | 'Master Sun's Military Methods' | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese military texts |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

|

|

|

The Art of War is an ancient Chinese military treatise dating from the Late Spring and Autumn Period (roughly 5th century BC). The work, which is attributed to the ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu ('Master Sun', also spelled Sunzi), is composed of 13 chapters. Each one is devoted to an aspect of warfare and how it applies to military strategy and tactics. For almost 1,500 years it was the lead text in an anthology that would be formalised as the Seven Military Classics by Emperor Shenzong of Song in 1080. The Art of War remains the most influential strategy text in East Asian warfare[1] and has influenced both Eastern and Western military thinking, business tactics, legal strategy, lifestyles and beyond.

The book contained a detailed explanation and analysis of the Chinese military, from weapons and strategy to rank and discipline. Sun Tzu also stressed the importance of intelligence operatives and espionage to the war effort. Because Sun Tzu has long been considered to be one of history's finest military tacticians and analysts, his teachings and strategies formed the basis of advanced military training for centuries to come.

The book was translated into French and published in 1772 (re-published in 1782) by the French JesuitJean Joseph Marie Amiot. A partial translation into English was attempted by British officer Everard Ferguson Calthrop in 1905 under the title The Book of War. The first annotated English translation was completed and published by Lionel Giles in 1910.[2] Military and political leaders such as the Chinese communist revolutionary Mao Zedong, Japanese daimyōTakeda Shingen, Vietnamese general Vo Nguyen Giap, and American military general Norman Schwarzkopf Jr. have drawn inspiration from the book.

- 1History

- 3Quotations

- 4Cultural influence

- 5See also

- 6References

History[edit]

Text and commentaries[edit]

The Art of War is traditionally attributed to a military general from the late 6th century BC known as 'Master Sun' (Mandarin: 'Sunzi', earlier 'Sun Tzu'), though its earliest parts probably date to at least 100 years later.[3]Sima Qian's 1st century BC work Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji), the first of China's 24 dynastic histories, records an early Chinese tradition stating that a text on military matters was written by one 'Sun Wu' (孫武) from the State of Qi, and that this text had been read and studied by King Helü of Wu (r. 514–495 BC).[4] This text was traditionally identified with the received Master Sun's Art of War. The conventional view—which is still widely held in China—was that Sun Wu was a military theorist from the end of the Spring and Autumn period (776–471 BC) who fled his home state of Qi to the southeastern kingdom of Wu, where he is said to have impressed the king with his ability to train even dainty palace ladies in warfare and to have made Wu's armies powerful enough to challenge their western rivals in the state of Chu.[5]

The prominent strategist, poet, and warlord Cao Cao in the early 3rd century AD authored the earliest known commentary to the Art of War.[4] Cao's preface makes clear that he edited the text and removed certain passages, but the extent of his changes were unclear historically.[4]The Art of War appears throughout the bibliographical catalogs of the Chinese dynastic histories, but listings of its divisions and size varied widely.[4] In the early 20th century, the Chinese writer and reformer Liang Qichao theorized that the text was actually written in the 4th century BC by Sunzi's purported descendant Sun Bin, as a number of historical sources mention a military treatise he wrote.[4]

Authorship[edit]

Around the 12th century, some scholars began to doubt the historical existence of Sunzi, primarily on the grounds that he is not mentioned in the historical classic The Commentary of Zuo (Zuo zhuan 左傳), which mentions most of the notable figures from the Spring and Autumn period.[4] The name 'Sun Wu' (孫武) does not appear in any text prior to the Records of the Grand Historian,[6] and has been suspected to be a made-up descriptive cognomen meaning 'the fugitive warrior': the surname 'Sun' is glossed as the related term 'fugitive' (xùn遜), while 'Wu' is the ancient Chinese virtue of 'martial, valiant' (wǔ武), which corresponds to Sunzi's role as the hero's doppelgänger in the story of Wu Zixu.[7] Unlike Sun Wu, Sun Bin appears to have been an actual person who was a genuine authority on military matters, and may have been the inspiration for the creation of the historical figure 'Sunzi' through a form of euhemerism.[7]

Yinqueshan tomb discovery[edit]

In 1972, the Yinqueshan Han slips were discovered in two Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220) tombs near the city of Linyi in Shandong Province.[8] Among the many bamboo slip writings contained in the tombs, which had been sealed between 134 and 118 BC, respectively were two separate texts, one attributed to 'Sunzi', corresponding to the received text, and another attributed to Sun Bin, which explains and expands upon the earlier The Art of War by Sunzi.[9] The Sun Bin text's material overlaps with much of the 'Sunzi' text, and the two may be 'a single, continuously developing intellectual tradition united under the Sun name'.[10] This discovery showed that much of the historical confusion was due to the fact that there were two texts that could have been referred to as 'Master Sun's Art of War', not one.[9] The content of the earlier text is about one-third of the chapters of the modern The Art of War, and their text matches very closely.[8] It is now generally accepted that the earlier The Art of War was completed sometime between 500 and 430 BC.[9]

The 13 chapters[edit]

The Art of War is divided into 13 chapters (or piān); the collection is referred to as being one zhuàn ('whole' or alternatively 'chronicle').

| Chapter | Lionel Giles (1910) | R.L. Wing (1988) | Ralph D. Sawyer (1996) | Chow-Hou Wee (2003) | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Laying Plans | The Calculations | Initial Estimations | Detail Assessment and Planning (Chinese: 始計) | Explores the five fundamental factors (the Way, seasons, terrain, leadership, and management) and seven elements that determine the outcomes of military engagements. By thinking, assessing and comparing these points, a commander can calculate his chances of victory. Habitual deviation from these calculations will ensure failure via improper action. The text stresses that war is a very grave matter for the state and must not be commenced without due consideration. |

| II | Waging War | The Challenge | Waging War | Waging War (Chinese: 作戰) | Explains how to understand the economy of warfare and how success requires winning decisive engagements quickly. This section advises that successful military campaigns require limiting the cost of competition and conflict. |

| III | Attack by Stratagem | The Plan of Attack | Planning Offensives | Strategic Attack (Chinese: 謀攻) | Defines the source of strength as unity, not size, and discusses the five factors that are needed to succeed in any war. In order of importance, these critical factors are: Attack, Strategy, Alliances, Army and Cities. |

| IV | Tactical Dispositions | Positioning | Military Disposition | Disposition of the Army (Chinese: 軍形) | Explains the importance of defending existing positions until a commander is capable of advancing from those positions in safety. It teaches commanders the importance of recognizing strategic opportunities, and teaches not to create opportunities for the enemy. |

| V | Use of Energy | Directing | Strategic Military Power | Forces (Chinese: 兵勢) | Explains the use of creativity and timing in building an army's momentum. |

| VI | Weak Points and Strong | Illusion and Reality | Vacuity and Substance | Weaknesses and Strengths (Chinese: 虛實) | Explains how an army's opportunities come from the openings in the environment caused by the relative weakness of the enemy and how to respond to changes in the fluid battlefield over a given area. |

| VII | Maneuvering an Army | Engaging The Force | Military Combat | Military Maneuvers (Chinese: 軍爭) | Explains the dangers of direct conflict and how to win those confrontations when they are forced upon the commander. |

| VIII | Variation of Tactics | The Nine Variations | Nine Changes | Variations and Adaptability (Chinese: 九變) | Focuses on the need for flexibility in an army's responses. It explains how to respond to shifting circumstances successfully. |

| IX | The Army on the March | Moving The Force | Maneuvering the Army | Movement and Development of Troops (Chinese: 行軍) | Describes the different situations in which an army finds itself as it moves through new enemy territories, and how to respond to these situations. Much of this section focuses on evaluating the intentions of others. |

| X | Classification of Terrain | Situational Positioning | Configurations of Terrain | Terrain (Chinese: 地形) | Looks at the three general areas of resistance (distance, dangers and barriers) and the six types of ground positions that arise from them. Each of these six field positions offers certain advantages and disadvantages. |

| XI | The Nine Situations | The Nine Situations | Nine Terrains | The Nine Battlegrounds (Chinese: 九地) | Describes the nine common situations (or stages) in a campaign, from scattering to deadly, and the specific focus that a commander will need in order to successfully navigate them. |

| XII | Attack by Fire | The Fiery Attack | Incendiary Attacks | Attacking with Fire (Chinese: 火攻) | Explains the general use of weapons and the specific use of the environment as a weapon. This section examines the five targets for attack, the five types of environmental attack and the appropriate responses to such attacks. |

| XIII | Use of Spies | The Use of Intelligence | Employing Spies | Intelligence and Espionage (Chinese: 用間) | Focuses on the importance of developing good information sources, and specifies the five types of intelligence sources and how to best manage each of them. |

Quotations[edit]

Sun Tzu Quotes

Chinese[edit]

Verses from the book occur in modern daily Chinese idioms and phrases, such as the last verse of Chapter 3:

- 故曰:知彼知己,百戰不殆;不知彼而知己,一勝一負;不知彼,不知己,每戰必殆。

- Hence the saying: If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.

This has been more tersely interpreted and condensed into the Chinese modern proverb:

- 知己知彼,百戰不殆。 (Zhī jǐ zhī bǐ, bǎi zhàn bù dài.)

- If you know both yourself and your enemy, you can win numerous (literally, 'a hundred') battles without jeopardy.

English[edit]

Common examples can also be found in English use, such as verse 18 in Chapter 1:

- 兵者,詭道也。故能而示之不能,用而示之不用,近而示之遠,遠而示之近。

- All warfare is based on deception. Hence, when we are able to attack, we must seem unable; when using our forces, we must appear inactive; when we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far away; when far away, we must make him believe we are near.

This has been abbreviated to its most basic form and condensed into the English modern proverb:

- All warfare is based on deception.

Cultural influence[edit]

Military and intelligence applications[edit]

Across East Asia, The Art of War was part of the syllabus for potential candidates of military service examinations.

During the Sengoku period (c. 1467–1568), the Japanese daimyō named Takeda Shingen (1521–1573) is said to have become almost invincible in all battles without relying on guns, because he studied The Art of War.[11] The book even gave him the inspiration for his famous battle standard 'Fūrinkazan' (Wind, Forest, Fire and Mountain), meaning fast as the wind, silent as a forest, ferocious as fire and immovable as a mountain.

The translator Samuel B. Griffith offers a chapter on 'Sun Tzu and Mao Tse-Tung' where The Art of War is cited as influencing Mao's On Guerrilla Warfare, On the Protracted War and Strategic Problems of China's Revolutionary War, and includes Mao's quote: 'We must not belittle the saying in the book of Sun Wu Tzu, the great military expert of ancient China, 'Know your enemy and know yourself and you can fight a thousand battles without disaster.'[11]

During the Vietnam War, some Vietcong officers extensively studied The Art of War and reportedly could recite entire passages from memory.

General Võ Nguyên Giáp successfully implemented tactics described in The Art of War during the Battle of Dien Bien Phu ending major French involvement in Indochina and leading to the accords which partitioned Vietnam into North and South. General Võ, later the main PVA military commander in the Vietnam War, was an avid student and practitioner of Sun Tzu's ideas.[12] America's defeat there, more than any other event, brought Sun Tzu to the attention of leaders of American military theory.[12][13][14]

Finnish Field Marshal Mannerheim and general Aksel Airo were avid readers of Art of War. They both read it in French; Airo kept the French translation of the book on his bedside table in his quarters.[citation needed]

The Department of the Army in the United States, through its Command and General Staff College, lists The Art of War as one example of a book that may be kept at a military unit's library.[15]

The Art of War is listed on the Marine Corps Professional Reading Program (formerly known as the Commandant's Reading List). It is recommended reading for all United States Military Intelligence personnel.[16]

According to some authors, the strategy of deception from The Art of War was studied and widely used by the KGB: 'I will force the enemy to take our strength for weakness, and our weakness for strength, and thus will turn his strength into weakness'.[17] The book is widely cited by KGB officers in charge of disinformation operations in Vladimir Volkoff's novel Le Montage.

Application outside the military[edit]

The Art of War has been applied to many fields well outside of the military. Much of the text is about how to fight wars without actually having to do battle: It gives tips on how to outsmart one's opponent so that physical battle is not necessary. As such, it has found application as a training guide for many competitive endeavors that do not involve actual combat.

The Art of War is mentioned as an influence in the earliest known Chinese collection of stories about fraud (mostly in the realm of commerce), Zhang Yingyu's The Book of Swindles (Du pian xin shu 杜騙新書, ca. 1617), which dates to the late Ming dynasty.[18]

Many business books have applied the lessons taken from the book to office politics and corporate business strategy.[19][20][21] Many Japanese companies make the book required reading for their key executives.[22] The book is also popular among Western business circles citing its utilitarian value regarding management practices. Many entrepreneurs and corporate executives have turned to it for inspiration and advice on how to succeed in competitive business situations. The book has also been applied to the field of education.[23]

The Art of War has been the subject of legal books[24] and legal articles on the trial process, including negotiation tactics and trial strategy.[25][26][27][28]

The Art of War has also been applied in the world of sports. National Football League coach Bill Belichick is known to have read the book and used its lessons to gain insights in preparing for games.[29]Australiancricket as well as Brazilianassociation football coaches Luiz Felipe Scolari and Carlos Alberto Parreira are known to have embraced the text. Scolari made the Brazilian World Cup squad of 2002 study the ancient work during their successful campaign.[30].

In 2018 English youth soccer coach Liam Shannon launched Sun Tzu Soccer[31], a project based on his 2012 book 'Sun Tzu Soccer: The Art of War in Soccer Language & Scenarios'. The book is a direct translation of the 2003 Lionel Giles 'Barnes & Noble Classics'[32] edition of The Art of War in to soccer terminology. In January 2015, Shannon presented his work at the United Soccer Coaches (previously 'NSCAA') National Convention - the world's largest soccer convention - to a full audience[33]. Sun Tzu Soccer has been endorsed by fellow Sun Tzu author Mark McNeilly, who stated: 'Sun Tzu Soccer gives coaches and players a time-tested formula for victory on the soccer field.'[34]

The Art of War is often quoted while developing tactics and/or strategy in Electronic Sports. Particularly, one of the fundamental books about e-sports, 'Play To Win' by Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate David Sirlin, is actually just an analysis about possible applications of the ideas from The Art of War in modern Electronic Sports.

The Art of War was released in 2014 as an e-book companion alongside the Art of War DLC for Europa Universalis IV, a PC strategy game by Paradox Development Studios, with a foreword by Thomas Johansson.

Notable translations[edit]

Art Of War Sun Tzu

- Sun Tzu on the Art of War. Translated by Lionel Giles. London: Luzac and Company. 1910.

- The Art of War. Translated by Samuel B. Griffith. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1963. ISBN978-0-19-501476-1. Part of the UNESCO Collection of Representative Works.

- Sun Tzu, The Art of War. Translated by Thomas Cleary. Boston: Shambhala Dragon Editions. 1988. ISBN978-0877734529.

- The Art of Warfare. Translated by Roger Ames. Random House. 1993. ISBN978-0-345-36239-1..

- The Art of War. Translated by John Minford. New York: Viking. 2002. ISBN978-0-670-03156-6.

- The Art of War: Sunzi's Military Methods. Translated by Victor H. Mair. New York: Columbia University Press. 2007. ISBN978-0-231-13382-1.

- The Art of War: Spirituality for Conflict. Translated by Thomas Huynh. Skylight Paths Publishing. 2008. ISBN978-1594732447.

The book has been translated into Assamese by Utpal Datta and published by Asom Sahitya Sabha.

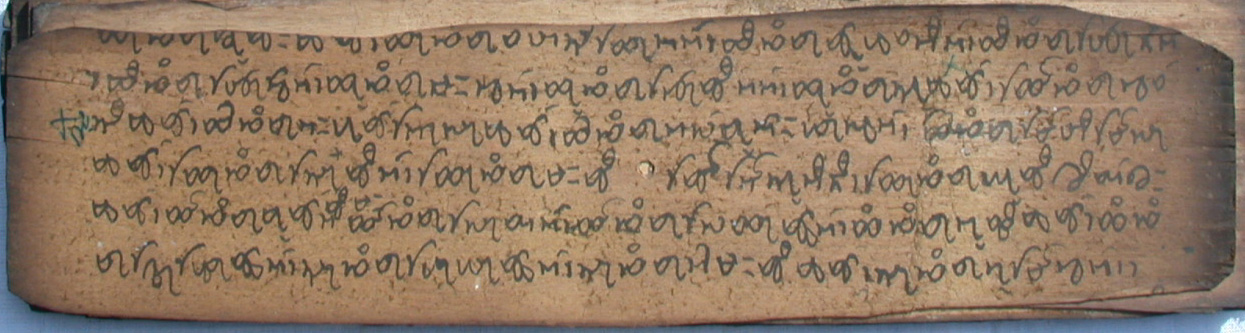

The book was translated into Manchu as ᠴᠣᠣᡥᠠᡳ

ᠪᠠᡳᡨᠠ

ᠪᡝ

ᡤᡳᠰᡠᡵᡝᠩᡤᡝ Wylie: Tchauhai paita be gisurengge,[35][36]Möllendorff: Coohai baita de gisurengge, Discourse on the art of War.[37]

The first Manchu translations of Chinese works were the Liu-t'ao 六韜, Su-shu 素書, and San-lueh 三略 – all Chinese military texts dedicated to the arts of war due to the Manchu interests in the topic, like Sun-Tzu's work The Art of War.[38][39] The military related texts which were translated into Manchu from Chinese were translated by Dahai.[40] Manchu translations of Chinese texts included the Ming penal code and military texts were performed by Dahai.[41] These translations were requested of Dahai by Nurhaci.[42] The military text Wu-tzu was translated into Manchu along with Sun-Tzu's work The Art of War.[43] Chinese history, Chinese law, and Chinese military theory classical texts were translated into Manchu during the rule of Hong Taiji in Mukden with Manchus placing significance upon military and governance related Chinese texts.[44] A Manchu translation was made of the military themed Chinese novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms.[45][46] Chinese literature, military theory and legal texts were translated into Manchu by Dahai and Erdeni.[47] The translations were ordered in 1629.[48][49] The translation of the military texts San-lüeh, Su-shu, and the Ta Ming hui-tien (the Ming law) done by Dahai was ordered by Nurhaci.[50] While it was mainly administrative and ethical guidance which made up most of San-lüeh and Su Shu, military science was indeed found in the Liu-t'ao and Chinese military manuals were eagerly translated by the Manchus and the Manchus were also attracted to the military content in Romance of the Three Kingdoms which is why it was translated.[51]

Another Manchu translation was made by Aisin Gioro Qiying.[52]

See also[edit]

Concepts[edit]

Books[edit]

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War) by Julius Caesar

- The Art of War by Niccolò Machiavelli

- The Book of Five Rings (Miyamoto Musashi)

- 'Seven Military Classics'

- 'Dream Pool Essays' by Shen Kuo

- 'Huolongjing' by Liu Bowen

- 'Hagakure' by Yamamoto Tsunetomo

- Epitoma rei militaris of Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus

- Guerrilla Warfare by Che Guevara

- On Protracted War by Mao Zedong

- On War by Carl von Clausewitz

- The Utility of Force by General Sir Rupert Smith

- Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T. E. Lawrence

- Infanterie Greift An by Erwin Rommel

- 'History of the Peloponnesian War' by Thucydides

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^Smith (1999), p. 216.

- ^Giles, LionelThe Art of War by Sun Tzu – Special Edition. Special Edition Books. 2007. p. 62.

- ^Lewis (1999), p. 604.

- ^ abcdefGawlikowski & Loewe (1993), p. 447.

- ^Mair (2007), pp. 12–13.

- ^Mair (2007), p. 9.

- ^ abMair (2007), p. 10.

- ^ abGawlikowski & Loewe (1993), p. 448.

- ^ abcGawlikowski & Loewe (1993), p. 449.

- ^Mark Edward Lewis (2005), quoted in Mair (2007), p. 18.

- ^ abGriffith, Samuel B.The Illustrated Art of War. 2005. Oxford University Press. pp. 17, 141–43.

- ^ abMcCready, Douglas. Learning from Sun Tzu, Military Review, May–June 2003.'Learning from Sun Tzu'. Archived from the original on 2011-10-11. Retrieved 2009-12-19.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^Interview with Dr. William Duiker, Conversation with Sonshi

- ^Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012). The Illustrated Art of War: Sun Tzu. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASINB00B91XX8U

- ^Army, U. S. (1985). Military History and Professional Development. U. S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute. 85-CSI-21 85.

- ^'Messages'.

- ^Yevgenia Albats and Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia – Past, Present, and Future. 1994. ISBN0-374-52738-5, chapter Who was behind perestroika?

- ^'Search Results book of swindles Columbia University Press'.

- ^Michaelson, Gerald. 'Sun Tzu: The Art of War for Managers; 50 Strategic Rules.' Avon, MA: Adams Media, 2001

- ^McNeilly, Mark. 'Sun Tzu and the Art of Business : Six Strategic Principles for Managers. New York:Oxford University Press, 1996.

- ^Krause, Donald G. 'The Art of War for Executives: Ancient Knowledge for Today's Business Professional.' New York: Berkley Publishing Group, 1995.

- ^Kammerer, Peter. 'The Art of Negotiation.' South China Morning Post (April 21, 2006) p. 15

- ^Jeffrey, D (2010). 'A Teacher Diary Study to Apply Ancient Art of War Strategies to Professional Development'. The International Journal of Learning. 7 (3): 21–36.

- ^Barnhizer, David. The Warrior Lawyer: Powerful Strategies for Winning Legal Battles Irvington-on-Hudson, NY: Bridge Street Books, 1997.

- ^Balch, Christopher D., 'The Art of War and the Art of Trial Advocacy: Is There Common Ground?' (1991), 42 Mercer L. Rev. 861–73

- ^Beirne, Martin D. and Scott D. Marrs, The Art of War and Public Relations: Strategies for Successful Litigation

- ^Pribetic, Antonin I., 'The Trial Warrior: Applying Sun Tzu's The Art of War to Trial Advocacy' April 21, 2007,

- ^Solomon, Samuel H., 'The Art of War: Pursuing Electronic Evidence as Your Corporate Opportunity'

- ^'Put crafty Belichick's patriot games down to the fine art of war'. The Sydney Morning Herald. 2005-02-04.

- ^Winter, Henry (June 29, 2006). 'Mind games reach new high as Scolari studies art of war'. Irish Independent.

- ^'Sun Tzu Soccer 📜⚽️ (@SunTzuSoccer) Twitter'. twitter.com.

- ^https://www.amazon.com/Art-Barnes-Noble-Classics-Paperback/dp/B00FKYHJ96

- ^'2015 NSCAA Convention'. www.eiseverywhere.com.

- ^https://www.facebook.com/SunTzuSoccer/posts/398356927441048?__xts__[0]=68.ARB8HwFAmpfB9wFBRIYVNQnW0Nn5hJJsDvH9Nd4JQFotLDTQ_HnnolNtmWF-tkSX1hDnecYCAA_w-tgVblT36WMjslDF_dc3uoAKb2jK5e5KCtQORlUFXDAnbiC-OKknTYrcV5QL-y0Ys9LlMV8WxXoQfcYHKP82WnyesokNrtaT22_uOHyrLIAp5J2VH5TBOxvdn3c3Un8_iBF3_raMN7abjqpkAKH1QoqAwXNo0l7gyTX-qarK-m8ic253BtAffbP1-0OHdV7yhbeanwC3SnNkJU-vxiTAwgAtdLRTwl2PuwwR49I-gw8eWArkValLdusK8P2OlomYKGOYPuoNo8k&__tn__=-R

- ^Shou-p'ing Wu Ko (1855). Translation (by A. Wylie) of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese grammar of the Manchu Tartar language (by Woo Kĭh Show-ping, revised and ed. by Ching Ming-yuen Pei-ho) with intr. notes on Manchu literature. p. 39.

- ^http://library.umac.mo/ebooks/b31043252.pdf

- ^Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. North China Branch, Shanghai (1890). Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Kelly & Walsh. pp. 40–.

- ^Early China. Society for the Study of Early China. 1975. p. 53.

- ^Durrant, Stephen (1977). “Manchu Translations of Chou Dynasty Texts”. Early China 3. [Cambridge University Press, Society for the Study of Early China]: 52–54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23351361.

- ^Sin-wai Chan (2009). A Chronology of Translation in China and the West: From the Legendary Period to 2004. Chinese University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN978-962-996-355-2.

- ^Peter C Perdue (30 June 2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press. pp. 122–. ISBN978-0-674-04202-5.

- ^Frederic Wakeman Jr. (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 44–. ISBN978-0-520-04804-1.

- ^Early China. Society for the Study of Early China. 1977. p. 53.

- ^Claudine Salmon (13 November 2013). Literary Migrations: Traditional Chinese Fiction in Asia (17th-20th Centuries). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 94–. ISBN978-981-4414-32-6.

- ^Cultural Hybridity in Manchu Bannermen Tales (zidishu). ProQuest. 2007. pp. 25–. ISBN978-0-549-44084-0.

- ^West, Andrew. 'The Textual History of Sanguo Yanyi: The Manchu Translation'. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^Arthur W. Hummel (1991). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing period: 1644–1912. SMC publ. p. vi. ISBN978-957-638-066-2.

- ^Shou-p'ing Wu Ko (1855). Translation (by A. Wylie) of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese grammar of the Manchu Tartar language (by Woo Kĭh Show-ping, revised and ed. by Ching Ming-yuen Pei-ho) with intr. notes on Manchu literature. pp. xxxvi–.

- ^Translation of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese Grammar of the Manchu Tartar Language; with introductory notes on Manchu Literature: (translated by A. Wylie.). Mission Press. 1855. pp. xxxvi–.

- ^http://www.dartmouth.edu/~qing/WEB/DAHAI.html

- ^Durrant, Stephen. 1979. “Sino-manchu Translations at the Mukden Court”. Journal of the American Oriental Society 99 (4). American Oriental Society: 653–61. doi:10.2307/601450. https://www.jstor.org/stable/601450?seq=2 pp. 654–56.

- ^Soldierly Methods: Vade Mecum for an Iconoclastic Translation of Sun Zi bingfa (Art of War). p. 82

Further reading[edit]

- Gawlikowski, Krzysztof; Loewe, Michael (1993). 'Sun tzu ping fa 孫子兵法'. In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 446–55. ISBN978-1-55729-043-4.

- Graff, David A. (2002). Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900. Warfare and History. London: Routledge. ISBN978-0415239554.

- Griffith, Samuel (2005). Sun Tzu: The Illustrated Art of War. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0195189995.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (1999). 'Warring States Political History'. In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 587–650. ISBN978-0-521-47030-8.

- Mair, Victor H. (2007). The Art of War: Sun Zi's Military Methods. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN978-0-231-13382-1.

- Smith, Kidder (1999). 'The Military Texts: The Sunzi'. In de Bary, Wm. Theodore (ed.). Sources of Chinese Tradition: From Earliest Times to 1600, Volume 1 (2nd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 213–24. ISBN978-0-231-10938-3.

- Yuen, Derek M. C. (2014). Deciphering Sun Tzu: How to Read 'The Art of War'. Oxford University Press. ISBN9780199373512.

- Вєдєнєєв, Д. В.; Гавриленко, О. А.; Кубіцький, С. О. (2017). Остроухова, В. В. (ed.). Еволюція воєнного мистецтва: у 2 ч.

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Art of War |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sun Tzu. |

- The Art of War Chinese-English bilingual edition, Chinese Text Project

- The Art of War translated by Lionel Giles (1910), various formats. The original book is partly written in Chinese, so PDF format is generally preferable. Also available from Project Gutenberg and Librivox below.

- The Art of War translated by Lionel Giles (1910) at Project Gutenberg

- The Book of War translated by E.F. Calthrop (1908) at Project Gutenberg

- The Art of War public domain audiobook at LibriVox (English and Chinese original available)

- Sun Tzu's Art of War at Sonshi

- Sun Tzu and Information Warfare at the Institute for National Strategic Studies of National Defense University

- The Art of War illustrated version, on Theoriq.com

Statue of Sun Tzu in Yurihama, Tottori, in Japan | |

| Born | 544 BC (traditional) Qi or Wu, Zhou Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Died | 496 BC (traditional) |

| Occupation | Military general, tactician, writer, philosopher |

| Period | Spring and Autumn |

| Subject | Military strategy |

| Notable works | The Art of War |

| Sun Tzu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

'Sun Tzu' in ancient seal script (top), regularTraditional (middle) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 孫子 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 孙子 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wade–Giles | Sun¹ Tzŭ³ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Sūnzǐ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | 'Master Sun' | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sun Wu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wade–Giles | Sun¹ Wu³ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Sūn Wǔ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Changqing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wade–Giles | Chʻang²-chʻing¹ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Chángqīng | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Tôn Vũ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 孫武 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 손무 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 孫武 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 孫武 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | そんぶ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sun Tzu (/ˈsuːnˈdzuː/;[1]Chinese: 孫子; Pinyin transliteration Sunzi) was a Chinese general, military strategist, writer and philosopher who lived in the Eastern Zhou period of ancient China. Sun Tzu is traditionally credited as the author of The Art of War, an influential work of military strategy that has affected Western and East Asian philosophy and military thinking. His works focus much more on alternatives to battle, such as stratagem, delay, the use of spies and alternatives to war itself, the making and keeping of alliances, the uses of deceit and a willingness to submit, at least temporarily, to more powerful foes.[2] Sun Tzu is revered in Chinese and East Asian culture as a legendary historical and military figure. His birth name was Sun Wu and he was known outside of his family by his courtesy nameChangqing.[citation needed] The name Sun Tzu by which he is best known in the Western World is an honorific which means 'Master Sun'.

Sun Tzu's historicity is uncertain. The Han dynasty historian Sima Qian and other traditional Chinese historians placed him as a minister to King Helü of Wu and dated his lifetime to 544–496 BC. Modern scholars accepting his historicity place the extant text of The Art of War in the later Warring States period based on its style of composition and its descriptions of warfare.[3] Traditional accounts state that the general's descendant Sun Bin wrote a treatise on military tactics, also titled The Art of War. Since Sun Wu and Sun Bin were referred to as Sun Tzu in classical Chinese texts, some historians believed them identical, prior to the rediscovery of Sun Bin's treatise in 1972.

Sun Tzu's work has been praised and employed in East Asian warfare since its composition. During the twentieth century, The Art of War grew in popularity and saw practical use in Western society as well. It continues to influence many competitive endeavors in the world, including culture, politics, business and sports, as well as modern warfare.[4][5][6][7]

Free Mortal Kombat Arcade Kollection Product Code 0MMX5-9PQPN-X2M50 First Come First Serve. I dont think this will work on steam i got it off amazon game downloads so if you can get from there here ya go. Mortal Kombat Arcade Kollection is a set of three games: Mortal Kombat, Mortal Kombat 2 and Ultimate Mortal Kombat 3. Originally, the game appeared in the 90s of the twentieth century. The game was developed by studio Other Ocean. Experience the deadliest tournament with all the kombatants and their. 116 rows Mortal Kombat Arcade Kollection Serial Numbers. Convert Mortal Kombat Arcade Kollection trail version to full software. Mortal kombat arcade moves.

- 1Life

Life[edit]

The oldest available sources disagree as to where Sun Tzu was born. The Spring and Autumn Annals states that Sun Tzu was born in Qi,[8] while Sima Qian's later Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) states that Sun Tzu was a native of Wu.[9] Both sources agree that Sun Tzu was born in the late Spring and Autumn period and that he was active as a general and strategist, serving kingHelü of Wu in the late sixth century BC, beginning around 512 BC. Sun Tzu's victories then inspired him to write The Art of War. The Art of War was one of the most widely read military treatises in the subsequent Warring States period, a time of constant war among seven ancient Chinese states – Zhao, Qi, Qin, Chu, Han, Wei, and Yan – who fought to control the vast expanse of fertile territory in Eastern China.[10]

Free download iscii devanagari font for microsoft. Welcome to DevanagariFonts, The largest and unique site that is completely dedicated to providing you easy and free download of Devanagari fonts. With more than 283 free Devanagari (Hindi, Nepali, Marathi, Sanskrit.) fonts, you can download almost any Devanagari font you want.

One of the more well-known stories about Sun Tzu, taken from Sima Qian, illustrates Sun Tzu's temperament as follows: Before hiring Sun Tzu, the King of Wu tested Sun Tzu's skills by commanding him to train a harem of 360 concubines into soldiers. Sun Tzu divided them into two companies, appointing the two concubines most favored by the king as the company commanders. When Sun Tzu first ordered the concubines to face right, they giggled. In response, Sun Tzu said that the general, in this case himself, was responsible for ensuring that soldiers understood the commands given to them. Then, he reiterated the command, and again the concubines giggled. Sun Tzu then ordered the execution of the king's two favored concubines, to the king's protests. He explained that if the general's soldiers understood their commands but did not obey, it was the fault of the officers. Sun Tzu also said that, once a general was appointed, it was his duty to carry out his mission, even if the king protested. After both concubines were killed, new officers were chosen to replace them. Afterwards, both companies, now well aware of the costs of further frivolity, performed their maneuvers flawlessly.[11]

Sima Qian claimed that Sun Tzu later proved on the battlefield that his theories were effective (for example, at the Battle of Boju), that he had a successful military career, and that he wrote The Art of War based on his tested expertise.[11] However, the Zuozhuan, a historical text written centuries earlier than the Shiji, provides a much more detailed account of the Battle of Boju, but does not mention Sun Tzu at all.[12]

Historicity[edit]

Beginning around the 12th century, some scholars began to doubt the historical existence of Sun Tzu, primarily on the grounds that he is not mentioned in the historical classic Zuo zhuan, which mentions most of the notable figures from the Spring and Autumn period.[13] The name 'Sun Wu' (孫武) does not appear in any text prior to the Shiji,[14] and may have been a made-up descriptive cognomen meaning 'the fugitive warrior': the surname 'Sun' can be glossed as the related term 'fugitive' (xùn遜), while 'Wu' is the ancient Chinese virtue of 'martial, valiant' (wǔ武), which corresponds to Sun Tzu's role as the hero's doppelgänger in the story of Wu Zixu.[15] The only historical battle attributed to Sun Tzu, the Battle of Boju, has no record of him fighting in that battle.[16]

Skeptics cite possible historical inaccuracies and anachronisms in the text, and that the book was actually a compilation from different authors and military strategists. Attribution of the authorship of The Art of War varies among scholars and has included people and movements including Sun; Chu scholar Wu Zixu; an anonymous author; a school of theorists in Qi or Wu; Sun Bin; and others.[17] Sun Bin appears to have been an actual person who was a genuine authority on military matters, and may have been the inspiration for the creation of the historical figure 'Sun Tzu' through a form of euhemerism.[15] The name Sun Wu does appear in later sources such as the Shiji and the Wu Yue Chunqiu, but were written centuries after Sun Tzu's era.[18]

The use of the strips in other works however, such as The Methods of the Sima is considered proof of Sun Tzu's historical priority.[19] According to Ralph Sawyer, it is very likely Sun Tzu did exist and not only served as a general but also wrote the core of the book that bears his name.[20] It is argued that there is a disparity between the large-scale wars and sophisticated techniques detailed in the text and the more primitive small-scale battles that many believe predominated in China during the 6th century BC. Against this, Sawyer argues that the teachings of Sun Wu were probably taught to succeeding generations in his family or a small school of disciples, which eventually included Sun Bin. These descendants or students may have revised or expanded upon certain points in the original text.[20]

Skeptics who identify issues with the traditionalist view point to possible anachronisms in The Art of War including terms, technology (such as anachronistic crossbows and the unmentioned cavalry), philosophical ideas, events, and military techniques that should not have been available to Sun Wu.[21][22] Additionally, there are no records of professional generals during the Spring and Autumn period; these are only extant from the Warring States period, so there is doubt as to Sun Tzu's rank and generalship.[22] This caused much confusion as to when The Art of War was actually written. The first traditional view is that it was written in 512 BC by the historical Sun Wu, active in the last years of the Spring and Autumn period (c. 722–481 BC). A second view, held by scholars such as Samuel Griffith, places The Art of War during the middle to late Warring States period (c. 481–221 BC). Finally, a third school claims that the slips were published in the last half of the 5th century BC; this is based on how its adherents interpret the bamboo slips discovered at Yinque Shan in 1972 AD.[23]

The Art of War[edit]

The Art of War is traditionally ascribed to Sun Tzu. It presents a philosophy of war for managing conflicts and winning battles. It is accepted as a masterpiece on strategy and has been frequently cited and referred to by generals and theorists since it was first published, translated, and distributed internationally.[24]

There are numerous theories concerning when the text was completed and concerning the identity of the author or authors, but archeological recoveries show The Art of War had taken roughly its current form by at least the early Han.[25] Because it is impossible to prove definitively when the Art of War was completed before this date, the differing theories concerning the work's author or authors and date of completion are unlikely to be completely resolved.[26] Some modern scholars believe that it contains not only the thoughts of its original author but also commentary and clarifications from later military theorists, such as Li Quan and Du Mu.

Of the military texts written before the unification of China and Shi Huangdi's subsequent book burning in the second century BC, six major works have survived. During the much later Song dynasty, these six works were combined with a Tang text into a collection called the Seven Military Classics. As a central part of that compilation, The Art of War formed the foundations of orthodox military theory in early modern China. Illustrating this point, the book was required reading to pass the tests for imperial appointment to military positions.[27]

Sun Tzu's The Art of War uses language that may be unusual in a Western text on warfare and strategy.[28] For example, the eleventh chapter states that a leader must be 'serene and inscrutable' and capable of comprehending 'unfathomable plans'. The text contains many similar remarks that have long confused Western readers lacking an awareness of the East Asian context. The meanings of such statements are clearer when interpreted in the context of Taoist thought and practice. Sun Tzu viewed the ideal general as an enlightened Taoist master, which has led to The Art of War being considered a prime example of Taoist strategy.

The book has also become popular among political leaders and those in business management. Despite its title, The Art of War addresses strategy in a broad fashion, touching upon public administration and planning. The text outlines theories of battle, but also advocates diplomacy and the cultivation of relationships with other nations as essential to the health of a state.[24]

On April 10, 1972, the Yinqueshan Han Tombs were accidentally unearthed by construction workers in Shandong.[29][30] Scholars uncovered a collection of ancient texts written on unusually well-preserved bamboo slips. Among them were The Art of War and Sun Bin's Military Methods.[30] Although Han dynasty bibliographies noted the latter publication as extant and written by a descendant of Sun, it had previously been lost. The rediscovery of Sun Bin's work is regarded as extremely important by scholars, both because of Sun Bin's relationship to Sun Tzu and because of the work's addition to the body of military thought in Chinese late antiquity.[31] The discovery as a whole significantly expanded the body of surviving Warring States military theory. Sun Bin's treatise is the only known military text surviving from the Warring States period discovered in the twentieth century and bears the closest similarity to The Art of War of all surviving texts.

Legacy[edit]

Sun Tzu's Art of War has influenced many notable figures. The Chinese historian Sima Qian recounted that China's first historical emperor, Qin's Shi Huangdi, considered the book invaluable in ending the time of the Warring States. In the 20th century, the Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong partially credited his 1949 victory over Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang to The Art of War. The work strongly influenced Mao's writings about guerrilla warfare, which further influenced communist insurgencies around the world.[32]

The Art of War was introduced into Japan c. AD 760 and the book quickly became popular among Japanese generals. Through its later influence on Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu,[32] it significantly affected the unification of Japan in the early modern era. Before the Meiji Restoration, mastery of its teachings was honored among the samurai and its teachings were both exhorted and exemplified by influential daimyōs and shōguns. It remained popular among the Imperial Japanese armed forces. The Admiral of the FleetTōgō Heihachirō, who led Japan's forces to victory in the Russo-Japanese War, who was an avid reader of Sun Tzu.[33]

Ho Chi Minh translated the work for his Vietnamese officers to study. His general Võ Nguyên Giáp, the strategist behind victories over French and American forces in Vietnam, was likewise an avid student and practitioner of Sun Tzu's ideas.[34][35][36]

The Art Of War Sun Tzu Summary

America's Asian conflicts against Japan, North Korea, and North Vietnam brought Sun Tzu to the attention of American military leaders. The Department of the Army in the United States, through its Command and General Staff College, has directed all units to maintain libraries within their respective headquarters for the continuing education of personnel in the art of war. The Art of War is mentioned as an example of works to be maintained at each facility, and staff duty officers are obliged to prepare short papers for presentation to other officers on their readings.[37] Similarly, Sun Tzu's Art of War is listed on the Marine Corps Professional Reading Program.[38] During the Gulf War in the 1990s, both Generals Norman Schwarzkopf Jr. and Colin Powell employed principles from Sun Tzu related to deception, speed, and striking one's enemy's weak points.[32] However, the United States and other Western countries have been criticised for not truly understanding Sun Tzu's work and not appreciating The Art of War within the wider context of Chinese society.[39]

Daoist rhetoric is a component incorporated in the Art of War. According to Steven C. Combs in 'Sun-zi and the Art of War: The Rhetoric of Parsimony',[40] warfare is 'used as a metaphor for rhetoric, and that both are philosophically based arts.'[40] Combs writes 'Warfare is analogous to persuasion, as a battle for hearts and minds.'[40] The application of The Art of War strategies throughout history is attributed to its philosophical rhetoric. Daoism is the central principle in the Art of War. Combs compares ancient Daoist Chinese to traditional Aristotelian rhetoric, notably for the differences in persuasion. Daoist rhetoric in the art of war warfare strategies is described as 'peaceful and passive, favoring silence over speech'.[40] This form of communication is parsimonious. Parsimonious behavior, which is highly emphasized in The Art of War as avoiding confrontation and being spiritual in nature, shapes basic principles in Daoism.[41]

Mark McNeilly writes in Sun Tzu and the Art of Modern Warfare that a modern interpretation of Sun and his importance throughout Chinese history is critical in understanding China's push to becoming a superpower in the twenty-first century. Modern Chinese scholars explicitly rely on historical strategic lessons and The Art of War in developing their theories, seeing a direct relationship between their modern struggles and those of China in Sun Tzu's time. There is a great perceived value in Sun Tzu's teachings and other traditional Chinese writers, which are used regularly in developing the strategies of the Chinese state and its leaders.[42]

In 2008, the Chinese television producer Zhang Jizhong adapted Sun Tzu's life story into a 40-episode historical drama television series entitled Bing Sheng, starring Zhu Yawen as Sun Tzu.[43]

In 2018 English youth soccer coach Liam Shannon launched Sun Tzu Soccer[44], a project based on his 2012 book Sun Tzu Soccer: The Art of War in Soccer Language & Scenarios. The book is a direct translation of the 2003 Lionel Giles and Barnes & Nobel Classic edition of The Art of War, translated in to soccer terminology. Shannon presented his work at the United Soccer Coaches National Convention on January 15th, 2015, to a full audience.[45] Sun Tzu Soccer has been endorsed by fellow Sun Tzu author Mark McNeilly, who stated: 'Sun Tzu Soccer gives coaches and players a time-tested formula for victory on the soccer field.'[46]

Notes[edit]

- ^'Sun Tzu'. Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (2013).

- ^Ancient warfare edited by John Carman and Anthony Harding, page 41

- ^Sawyer, Ralph D. (2007), The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China, New York: Basic Books, pp. 421–22, ISBN978-0-465-00304-4

- ^Scott, Wilson (7 March 2013), 'Obama meets privately with Jewish leaders', The Washington Post, Washington, D.C., archived from the original on 24 July 2013, retrieved 22 May 2013Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^'Obama to challenge Israelis on peace', United Press International, 8 March 2013, retrieved 22 May 2013

- ^Garner, Rochelle (16 October 2006), 'Oracle's Ellison Uses 'Art of War' in Software Battle With SAP', Bloomberg, archived from the original on October 20, 2015, retrieved 18 May 2013Cite uses deprecated parameter

dead-url=(help); Invaliddead-url=Yes(help) - ^Hack, Damon (3 February 2005), 'For Patriots' Coach, War Is Decided Before Game', The New York Times, retrieved 18 May 2013

- ^Sawyer 2007, p. 151.

- ^Sawyer 2007, p. 153.

- ^McNeilly 2001, pp. 3–4.

- ^ abBradford 2000, pp. 134–35.

- ^Zuo Qiuming, 'Duke Ding', Zuo Zhuan (in Chinese and English), XI

- ^Gawlikowski & Loewe (1993), p. 447.

- ^Mair (2007), p. 9.

- ^ abMair, Victor H. (2007). The Art of War: Sun Zi's Military Methods. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN978-0-231-13382-1.

- ^Worthington, Daryl (2015-03-13). 'The Art of War'. New Historian. Archived from the original on March 3, 2019.Cite uses deprecated parameter

dead-url=(help); Invaliddead-url=Yes(help) March 13, 2015 - ^Sawyer 2005, pp. 34–35.

- ^Sawyer 2007, pp. 176–77.

- ^Sawyer 1994, pp. 149–50.

- ^ abSawyer 2007, pp. 150–51.

- ^Yang, Sang. The Art of War. Wordsworth Editions Ltd (December 5, 1999). pp. 14–15. ISBN978-1853267796

- ^ abSzczepanski, Kallie. 'Sun Tzu and the Art of War'. Asian History. February 04, 2015

- ^Morrow, Nicholas (February 4, 2015). 'Sun Tzu, The Art of War (c. 500–300 B.C.)'. Classics of Strategy.

- ^ abMcNeilly 2001, p. 5.

- ^Sawyer 2007, p. 423.

- ^Sawyer 2007, p. 150.

- ^Sawyer 1994, pp. 13–14.

- ^Simpkins & Simpkins 1999, pp. 131–33.

- ^Yinqueshan Han Bamboo Slips (in Chinese), Shandong Provincial Museum, 24 April 2008, archived from the original on 29 October 2013Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^ abClements, Jonathan (21 June 2012), The Art of War: A New Translation, Constable & Robinson Ltd, pp. 77–78, ISBN978-1-78033-131-7

- ^朱文章(Sydney Wen-Jang Chu) ; 李承禹(Cheng-Yu Lee) Just another Masterpiece: the Differences between Sun Tzu's the Art of War and Sun Bin's the Art of War. http://www.airitilibrary.com/Publication/alDetailedMesh?docid=P20121108003-201301-201302010022-201302010022-59-73

- ^ abcMcNeilly 2001, pp. 6–7.

- ^Tung 2001, p. 805.

- ^'Interview with Dr. William Duiker', Sonshi.com, retrieved 5 February 2011

- ^McCready, Douglas M. (May–June 2003), 'Learning from Sun Tzu', Military Review, archived from the original on 2012-06-29Cite uses deprecated parameter

dead-url=(help) - ^Forbes, Andrew & Henley, David (2012), The Illustrated Art of War: Sun Tzu, Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books, ASINB00B91XX8U

- ^U.S. Army (c. 1985), Military History and Professional Development, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute, 85-CSI-21 85. The Art of War is mentioned for each unit's acquisition in 'Military History Libraries for Duty Personnel' on page 18.

- ^'Marine Corps Professional Reading Program', U.S. Marine Corps

- ^Hall, Gavin. 'Review – Deciphering The Art of War'. LSE Review of Books. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ abcdCombs, Steven C. (August 2000). 'Sun-zi and the Art of War: The Rhetoric of Parsimony'. Quarterly Journal of Speech. 86 (3): 276–94. doi:10.1080/00335630009384297.

- ^Galvany, Albert (October 2011). 'Philosophy, Biography, and Anecdote: On the Portrait of Sun Wu'. Philosophy East and West. 61 (4): 630–46. doi:10.1353/pew.2011.0059.

- ^McNeilly 2001, p. 7.

- ^Bing Sheng (in Chinese), sina.com

- ^https://twitter.com/SunTzuSoccer

- ^https://www.eiseverywhere.com/ehome/nscaa15/115agenda/?&

- ^https://www.facebook.com/SunTzuSoccer/posts/398356927441048?__xts__[0]=68.ARB8HwFAmpfB9wFBRIYVNQnW0Nn5hJJsDvH9Nd4JQFotLDTQ_HnnolNtmWF-tkSX1hDnecYCAA_w-tgVblT36WMjslDF_dc3uoAKb2jK5e5KCtQORlUFXDAnbiC-OKknTYrcV5QL-y0Ys9LlMV8WxXoQfcYHKP82WnyesokNrtaT22_uOHyrLIAp5J2VH5TBOxvdn3c3Un8_iBF3_raMN7abjqpkAKH1QoqAwXNo0l7gyTX-qarK-m8ic253BtAffbP1-0OHdV7yhbeanwC3SnNkJU-vxiTAwgAtdLRTwl2PuwwR49I-gw8eWArkValLdusK8P2OlomYKGOYPuoNo8k&__tn__=-R

References[edit]

Sun Tzu Citate

- Ames, Roger T. (1993). Sun-tzu: The Art of Warfare: The First English Translation Incorporating the Recently Discovered Yin-chʻüeh-shan Texts. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN978-0345362391.

- Bradford, Alfred S. (2000), With Arrow, Sword, and Spear: A History of Warfare in the Ancient World, Praeger Publishers, ISBN978-0-275-95259-4

- Gawlikowski, Krzysztof; Loewe, Michael (1993). 'Sun tzu ping fa 孫子兵法'. In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 446–55. ISBN978-1-55729-043-4.

- McNeilly, Mark R. (2001), Sun Tzu and the Art of Modern Warfare, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0-19-513340-0.

- Mair, Victor H. (2007). The Art of War: Sun Zi's Military Methods. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN978-0-231-13382-1.

- Sawyer, Ralph D. (1994), The Art of War, Westview Press, ISBN978-0-8133-1951-3.

- Sawyer, Ralph D. (2005), The Essential Art of War, Basic Books, ISBN978-0-465-07204-0.

- Sawyer, Ralph D. (2007), The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China, Basic Books, ISBN978-0-465-00304-4.

- Simpkins, Annellen & Simpkins, C. Alexander (1999), Taoism: A Guide to Living in the Balance, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN978-0-8048-3173-4.

- Tao, Hanzhang; Wilkinson, Robert (1998), The Art of War, Wordsworth Editions, ISBN978-1-85326-779-6.

- Tung, R. L. (2001), 'Strategic Management Thought in East Asia', in Warner, Malcolm (ed.), Comparative Management:Critical Perspectives on Business and Management, 3, Routledge.

External links[edit]

- Translations

- Works by Sun Tzu at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Sun Tzu at Internet Archive

- Works by Sun Tzu at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Sun Tzu's Art of War at Sonshi

- Sun Tzu and Information Warfare at the Institute for National Strategic Studies of National Defense University

- Sun Tzu sites

- Sun Tzu's Art of WarSonshi.com. Reviews of translations, interviews with translators, notices of activities.

- Sun TzuDMOZ Open Directory Project Collection of links to online translations and resources on Sun Tzu.

- Victory Over War Formed by the Denma Group to supplement their translation with notes, reviews, and discussion.